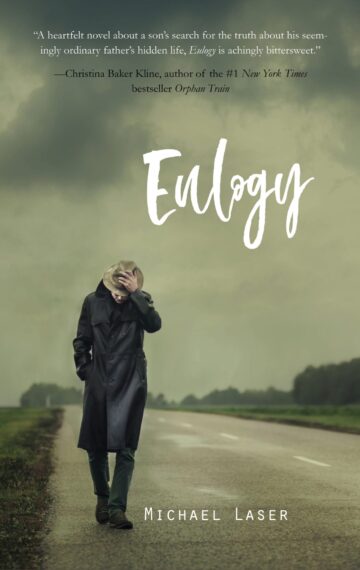

Just hours after delivering his father’s eulogy, Ken Weintraub learns that this hard-working, unassuming man spent three years in prison. Consumed by the astonishing news, Ken sets out to unravel the mystery. As he pries information from old friends, relatives, and others, he pieces together a portrait that’s full of contradictions. Was his father an assassin’s accomplice? A gullible victim? Or a heroic, loyal friend? Everywhere he turns, he hears stories that surprise him. Even when he thinks he knows the whole truth, there’s still more to learn.

“A heartfelt novel about a son’s search for the truth about his seemingly ordinary father’s hidden life, Eulogy is achingly bittersweet. As he begins asking questions he isn’t sure he wants to know the answers to, the son is forced to reassess everything he believes about the people he loves—and ultimately examine his own life choices and decisions. Quietly observed and richly absorbing.” —Christina Baker Kline, author of the #1 New York Times bestseller Orphan Train

“At the heart of this tender, engrossing novel are a father’s secrets, a son’s attempts to unearth them, and the son’s struggle to understand why so much was kept hidden from him. Absorbing and perceptive.” —Jane Bernstein, author of Loving Rachel and The Face Tells the Secret

“Eulogy captivates you almost immediately, with a subtlety that defies expectation. The story unfolds with humor and urgency, offering up a family secret (we all have ’em, though not quite like this) that slowly implodes. This book is a winner; it reminds you of the incredible power of the things that remain unsaid.” —Robert Edelstein, Author of Full Throttle: The Life and Fast Times of NASCAR Legend Curtis Turner

“A carefully crafted and inherently fascinating novel… Eulogy is a compelling and memorable read from first page to last.” — Midwest Book Review

EXCERPT:

I had written a eulogy on the plane. My father’s life has always struck me as epic in scope—the Depression, the war, his three careers and two wives—and I found it surprisingly comfortable to stand at the lectern and share these stories with his many friends and relatives. What I hadn’t anticipated was the stone in my throat. I’ve been preparing myself for his death for six years, ever since his first stroke, but I had to stop twice and recover the ability to speak.

“My father may have been the happiest man I ever met. What makes this interesting is that he went though so much that could have embittered him. Childhood poverty. A war and a near-fatal wound. His wife’s premature death. Two strokes. But I only saw him angry two or three times, and never heard him speak a resentful word.

“Many of you already know the stories I’m going to tell. But I’d like to honor him by remembering his life, together with all of you.

“He grew up in Williamsburg, back when only poor people lived there. My grandparents had a fruit stand and my grandfather gave music lessons, but they couldn’t afford to feed themselves and their children. My father spent a lot of time across the hall, with the Abneys—a ‘colored’ family, as he called them—who fed him and welcomed him to their parties, where he learned to dance. With his brother Sam, he explored the tunnels of the new subway line before the tracks were laid. Hot sweet potatoes cost five cents, he once told me. You’d break one in half and share it with a brother or sister. Then you’d suck it to get every last bit. That’s everything I know about his childhood.

“A neighbor helped get him a job making rosaries at a little shop called Muller’s. (When people said, ‘You made what?’ he would shrug and explain, ‘I needed a paycheck.’) He took pride in his craftsmanship. I loved watching him twist wire with his needle-nose pliers: his skill amazed me. The store was on Barclay Street, around the corner from the Woolworth Building, and the nuns who came in were fond of him. They may have assumed he was Italian; he always looked Italian to me. When he was recovering from his wounds in an army hospital, a novena was said for him. I finally looked up what that means: nine days of prayer. I’m guessing few Jews have received the honor.

“He enlisted in 1943, as soon as he turned eighteen. But he didn’t want to marry my mother until he came home, in case ‘something happened.’”

(My draft included the tale of the German soldier and the ring. I left it out because I didn’t want people to think of him that way: so powerless that his only recourse was to play dead.)

… “They gave him an IQ test and he did well. An officer asked him, ‘How would you like to serve in the Air Corps, soldier?’ Dad answered, ‘I don’t think I’d like to jump out of a plane.’ The officer said, ‘I didn’t ask you that.’ Next thing he knew, the guy had angrily stamped his papers with the word Infantry—the most dangerous place you could be.

“One other army story. Ten minutes before he got shot, he said to his friend Fred, ‘These mountains would be a terrible place to get hit. They’d never find you.’ And they didn’t find him, for twenty-four hours. He had sulfa drugs in his pack, and he took more than you were supposed to, to ward off infection.”

(He peed blood, I had written, but I left that unsaid.)

COMMENTS:

Where did this story come from?

I’d read a book called Beautiful Souls, by Eyal Press, about ordinary people who go against the rules because of a deep sense of conscience. The most memorable story, for me, was the one about the Swiss policeman who helped Jewish refugees cross over from Austria in 1938. I wanted to create a story like that: the story of an ordinary man, not a heroic type, who risks himself somehow to save someone else.

But I saw that there might be even more to the story. It’s not just that my hero did something brave, it’s that his children never knew about it, because he was ashamed and kept it a secret. Why was he ashamed? Because he spent three years in prison as a result of this one impulsive act.

The other source of Eulogy’s plot was the experience of delivering a eulogy for my father. At first it went smoothly, but as I told certain stories, I found that my throat locked. I couldn’t speak. That unexpected emotion turned into the heart of this book.

Is the story autobiographical? Not really. It’s true that I took some of the details of Morris’s biography straight from my father’s life—I love these stories, and wanted to bestow them on a beloved character—but Morris, the fictional father, is nothing like my father. And I don’t think I’m much like Ken, the son.